I’ve been on Music Vine’s roster since September 2019.

At first, it felt great. I felt validated, and I was making money too.

But by the end of 2020, I realized I had to remove my songs from the platform. And I want to share my experience so you can better decide if it’s right for you or not.

As far as I know, this is the most comprehensive Music Vine review from an artist’s perspective.

I include input from other Music Vine artists, share stats, and give you a behind-the-scenes look at this platform.

Figure out how to succeed. Stay encouraged and motivated. Download The One-Thing-A-Day Worksheet for FREE below.

Table of Contents

What Initially Attracted Me to Music Vine

In 2019, I was looking for a sync licensing company that would be a good fit for me. One that valued artists and also wanted my style of music in their library.

As I was researching Music Vine, I saw they linked to an open letter on Medium from the CEO, Lewis Foster.

He wrote about how companies in the music licensing world were devaluing artists’ music.

He said when companies charge a low annual fee for access to their entire library for unlimited use, they’re killing the licensing industry.

For example, companies charge filmmakers $200 a year and let them use whatever songs they want as many times as they want.

Forever.

These companies are basically Spotify-ing the sync licensing world.

“Spotify left a bitter enough taste for many musicians and that is a model for the personal consumption of music,” Foster said. “[Frankly], to attempt [to] apply the Spotify model with Spotify prices to commercial music licensing is beyond absurd.”

But how does this low-subscription model hurt the sync world and the artists in it?

Well, the amount of money their clients (filmmakers, music supervisors, producers, podcasters, etc.) spend on licensing songs represents the total value of the sync market.

And the higher the value of the market, the more the market allows artists to make a living wage from licensing.

Foster talked about it like a “highly pressurized container.”

“Without the air pressure, the container collapses, the professions perish,” he said.

“Now imagine puncturing that pressurized container. That’s essentially what happens when an aggressive business model seeks to capitalize rapidly by undermining the value of the market’s core asset (music).”

Charging less to license music undermines the value of the artists’ music.

This, Foster argues, is what Spotify did and continues to do to musicians.

And if the air keeps seeping out of this pressurized container, the artists breathing that air will start to suffocate.

Making reasonable money from licensing becomes less and less of a reality for musicians.

And yet, the companies causing this to happen continue to profit and grow.

But, you may ask, how are some artists doing well, apparently making a living, from these low-cost, one-size-fits-all subscription licensing companies?

Because, as Foster pointed out, it’s a fast burn.

“If you’re a part of the object that is piercing the container, you’re also going to be party to the blast from the air leak,” he said. “…If you sell something valuable but at a rock-bottom price, it’s going to sell a lot and fast, which will add up to something that appears reasonable. However, it’s crucial to realise that the air blast doesn’t last long.”

And this perspective compelled me to join Music Vine.

The fact that the dude who ran the company saw the problem when no one else seemed to.

It really sounded like Music Vine would stick to this ideology and continue to offer a pay-per-license model and avoid subscriptions.

But as it turned out, that was not the case. More on that below.

First, let me share my experience with this company.

My Experience With Music Vine

Music Vine accepted me into their roster in September of 2019, and I was pumped.

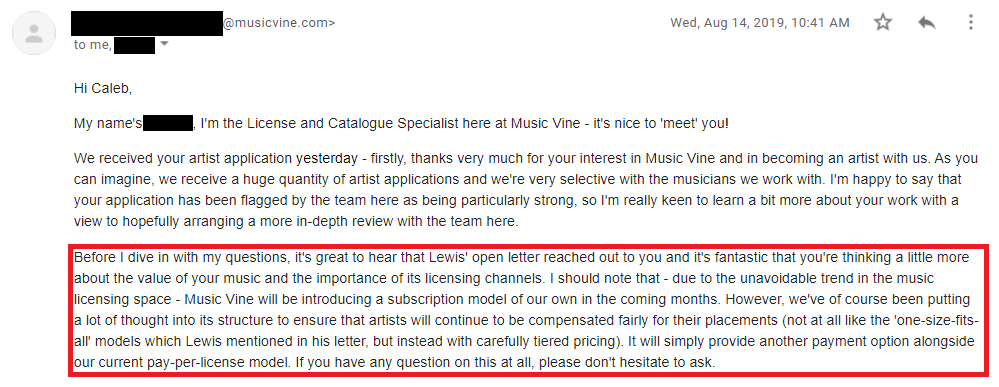

Right after I joined, my contact at the company (my “License & Catalogue Specialist”) welcomed me with professional excitement. The guy has been super easy to work with.

Before I applied, they made it clear I wasn’t allowed to work with sync licensing companies that offer a “one-size-fits-all subscription model.”

They said they’re “advocates of fair payment for musicians and a sustainable licensing industry.”

But right after I joined, my contact let me know Music Vine would be adding subscriptions.

This confused me as I had just read Foster’s open letter, which was one of the main reasons I liked them.

Yes, his Medium post addressed the one-size-fits-all option, but I felt like any subscription model was a step in that direction.

But it was good to hear that, despite the introduction of subscriptions, I would be “compensated fairly” for licenses.

So, I happily joined the roster, submitted every new song I released, and people started licensing my music.

I began making a little bit of money every month, and it felt really good. Finally, after years of being a struggling DIY musician, I was making consistent income from my music.

Then I thought, “I wonder who’s using my music and for what projects. Ima go look.”

So I signed into my account to see who was licensing my songs. But I couldn’t find any info about the end client or what projects my songs were being used in.

I emailed my contact and he informed me that even the company didn’t know — not unless the client decided to tell them.

This was disappointing because nowhere did I see this mentioned during the application process.

I let it slide and continued licensing my music, but that issue lodged itself in the back of my brain.

I continued making regular money, and that money paid for my one-song-at-a-time project, PHENOMENA.

Before Music Vine, I would have to run a Kickstarter or just straight-up ask people for donations.

So with Music Vine, it felt like I was getting paid fairly.

That was until a year later when I did a case study on my experience in sync licensing. And I found some interesting stats.

After a year with Music Vine, I realized I wasn’t being paid fairly. At all.

When I did the case study, I had 10 songs in their library and 58 total licenses. This included one-off licenses and licenses by subscription clients.

And after crunching the numbers…

I discovered I had made an average of roughly $3 per license.

I don’t need to tell you that that’s terrible pay.

But I will — that’s terrible pay for licensing my songs, allowing companies and creators to use my songs to sell their products and spread their messages.

Especially because I had no idea who these clients were.

But was this just me? Am I an outlier?

Or were other artists also making very little per license?

Other Musicians’ Experiences With Music Vine

To make sure this wasn’t just me, I reached out to some fellow Music Vine artists.

Singer-songwriter Joe Kaplow told me via an Instagram message that he makes consistent but small amounts of money from MV.

“My overall experience has been good only because I got one really good placement that grew my fan base in a major way,” he said.

He pointed out that all Music Vine did was make this song available for a music supervisor to license, as opposed to MV actively pitching his music.

And he wouldn’t have landed that sync placement without having his music on the platform.

But he said Music Vine and similar companies are not good for artists in the big picture.

He said he makes “about $1.50 per license.”

“Overall, I think companies like Music Vine are undermining the way artists can [get] paid from traditional licensing deals,” he said.

“Like, I’ve heard that the music supervisors who were paying $10k for placements 10 years ago are now asking the licensing companies to stop sending them music, [because] they can just buy a song for $50 from Music Vine.”

Even still, Kaplow said he’d rather “put my music up on Music Vine and hope.”

He plans to get sync placements that grow his fanbase and his career, then work up to the high-paying deals with well-known brands.

Sounds like an okay plan, but is it worth getting paid unfairly until then?

We could also look at singer-songwriter/producer/engineer John Lowell Anderson, who averages $2.93 per license on Music Vine.

And he told me he doesn’t “rely on [Music Vine] by any means.” In other words, MV isn’t one of his main income streams.

These artists seem to be leaving their music on Music Vine because, even though they get paid a couple of bucks per license, they’re at least making money and getting exposure.

And I get that. I’ve been making consistent money on the platform too, and it feels good. It feels fair.

But we can see by the numbers, Music Vine’s payouts are not fair to musicians.

And that’s not the only reason this company may not be good for indie artists…

Why I Removed My Songs From Music Vine

I decided to remove five of the 10 songs I had in Music Vine’s catalog.

Here are the main reasons I removed those songs:

- The clients are anonymous

- Unfair pay

- It normalizes the devaluing of music

I’ll go into each of these reasons in detail below.

But first, why did I remove only five of my songs?

I removed five songs that were much more meaningful to me. I spent hours upon hours writing, recording, and mixing these songs. Plus, they had very personal lyrics.

The five songs I left with Music Vine were four instrumentals and a cover song.

Don’t get me wrong, the songs still in MV’s catalog are meaningful to me. But I feel much more attached to my songs with lyrics.

So if I’m going to license personal songs, I want to get paid fairly and know where they’re going.

I won’t be submitting any more songs to MV, and I’m considering removing the five songs still on the platform.

Anonymous clients

When I joined the MV roster, I assumed I would know who was licensing my music. (And you know what they say about assuming).

At first, I thought I was cool with this. But after some time, I realized I didn’t feel comfortable with it.

I spent hours and days writing these songs, some of them having very vulnerable lyrics. Then I spent hours and days producing and mixing them at home. And then I hired an engineer to master them.

And it didn’t sit right with me that unknown companies were using my songs to sell their products, promote their message, and build their brand.

I want to know where my songs were ending up.

And granted, sometimes the client would share who they were. (For example, several jewelry companies licensed my song “Dancing On Magic”).

But most of the time, my voice and productions were supporting a company I knew nothing about.

Now, my contact at Music Vine did say the appeal of their platform to filmmakers is the ease of use. So that’s why MV doesn’t make the filmmakers state their client.

And he assured me clients are not allowed to use these songs in any “adult, offensive, or harmful material.”

Unfair pay

I really wanted Music Vine to be my main platform for licensing. But once I realized they were paying me about $3 per license, that was a dealbreaker.

To put this in context, let’s look at the industry average payout for a license.

In a free webinar I attended, the folks at Ari’s Take Academy shared the average payouts for a single license of a song depending on how it’s used:

So to realize I was earning an average of $3 to let a client use my song in their visual content was very disappointing.

Even the highest payouts I got (the one-off licenses by non-subscription clients) wouldn’t be any more than about $50.

On the other hand, my contact at Music Vine pointed out their subscription model was fairly new, and they projected it would grow, meaning artists would earn more per license.

“…The number of users has grown significantly [since you joined our roster] and we expect it to continue growing,” he told me in an email. “Meaning the amount of subscription earnings to be shared with our artists will also continue to increase.”

But for Music Vine artists to start getting paid fairly, the payouts need to make a drastic increase.

And I don’t see that happening.

It normalizes the devaluing of music in sync

The cost of many licenses on Music Vine are cheap. Many of their subscription plans are cheap.

Yes, the higher-tiered plans cost a filmmaker more, up to $6,000 a year. And songs licensed by those clients would pay the artist more.

But, according to my contact, “many users are on our smaller-tiered plans and so earnings aren’t always very significant.”

He did say the clients on the cheaper plans end up licensing more music. So the earnings for each license are less, but there are more of them.

But overall, I agree with Kaplow that Music Vine is undermining the sync licensing industry.

They’re normalizing unfair pay for artists, conditioning filmmakers to expect music to be cheap.

Music is becoming so easy to access at such a low cost, it’s in danger of becoming less appreciated.

Music is one of the main factors driving the emotion in visual content. So why are we musicians okay with getting paid the price of a coffee for a license?

I think Foster was right. Getting paid these small amounts is Spotify-ing the licensing industry.

Pros and Cons of Music Vine

Just in case you skipped to this section, here’s the good and bad of Music Vine in list form…

Pros:

- Not a huge library, so you have more chance of getting licensed

- Licenses can give you good exposure (although, in my experience, most do not)

- My contact person was super professional and easy to work with

Cons:

- Splits are not great (35% for non-exclusive tracks, 60% for exclusive tracks)

- Unfair pay to the artist (payouts typical average $1-3 per license)

- Anonymous licenses unless the client decides to enter their info

- Devaluing music in sync (conditioning filmmakers/music supervisors to expect music to be cheap)

As you can see, not a very good final score for Music Vine.

Final Thoughts

The reality is, MV pays so little, I felt I had to remove at least some of my songs.

I also don’t plan to submit any more songs to them in the near future (or ever).

I would advise you not to work with Music Vine. And I suggest you not work with any other companies who don’t value your music for what it’s worth.

And any company that pays a couple of bucks per license doesn’t value your music, no matter what they say.

As Foster said, “to apply the Spotify model with Spotify prices to commercial music licensing is beyond absurd.”

I agree.

Feel overwhelmed?

Download The One-Thing-A-Day Worksheet for free to…

- Map out where you’re going

- Figure out how to get there

- Discover what you can do today to move forward

Further reading

- Casino Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Betting Sites

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Casino Retrait Immédiat

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Gambling Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- Non Gamstop Casino Sites UK

- Slots Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Meilleur Casino En Ligne

- Beste Online Casino Nederland

- Non Gamstop Casino UK

- Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- UK Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Sports Betting Sites UK

- Slot Sites Uk

- Gokken Zonder Cruks

- Non Gamstop Casinos

- Non Gamstop Casinos UK

- UK Casino Sites Not On Gamstop

- UK Online Casinos Not On Gamstop

- Migliori Casino Non Aams

- Migliori App Casino Online

- Migliori Casino Non Aams

- Top 10 Casino En Ligne Belgique

- I Migliori Casino Non Aams

- Meilleur Site Pour Jouer Au Poker

- Paris Sportifs Crypto

- KYC 인증 없는 카지노

- Casino Live En Ligne Français

- 온라인홀덤

- Top Casino En Ligne

- Casino En Ligne

- Casino Italia Non Aams

- Casino En Ligne Français

- Migliori Siti Casino Non Aams 2026

- 카지노코인